ISSN: 1204-5357

ISSN: 1204-5357

Kiran Sahrawat

The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand

Postal Address: P.O. Box 31914, Wyndrum Avenue, Lower Hutt

Email: kiran.sahrawat@openpolytechnic.ac.nz

Dr. Kiran Sahrawat is a Senior Lecturer at the Centre of Accounting in The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand. Her areas of interest are Intellectual Capital and International Financial Reporting Standards (Financial Instruments).

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Internet Banking and Commerce

The new knowledge economies have highlighted the importance of intellectual capital (IC) and the imperative need to measure and manage their associated costs and benefits. Banks and financial institutions, which are rich in IC (human, customer, and social capital), are in danger of becoming subject to ‘IC walkouts’ if they resist accounting for the hidden value that exists in IC and its constituent elements. This paper discusses how New Zealand banks incur the cost of acquiring IC and realize the need to recognize related cost drivers. For banks in New Zealand, one of the most important sources of revenue or interest income is from mortgage business. This investigation looks at the value added by mobile mortgage managers (MMMs) and a possible model for measuring the IC vested in MMMs. Some of the issues and concerns explored should be of importance to accounting (management) academics. A number of potential problems that are identified suggest the need for more diversified research to develop an effective model for IC valuation that includes social networking and political underpinnings, in this age of globalization and value creation.

Intellectual capital, measurement, banks, maintenance, Mobile Mortgage Managers

It is increasingly stated by professional accountants, institutional investors, and e-accountants, especially of the new knowledge economies, that new financial and management accounting concepts and practices need to be established to acknowledge the intellectual capital (IC) of business enterprises. Whether it is in manufacturing or service or technology, the value vested in human IC cannot be ignored. This concept of measurement and management of IC costs is gaining importance in the service industries too. These industries include insurance companies, financial institutions, banks and companies based on high technology. Accountants from different countries, industries, companies and backgrounds agree that the focus should be shifted from IC measurement to another level of accounting for IC that is acceptable to auditors and accountants to fit in the financial reporting regime.

In New Zealand, banks are a special vehicle of the service industry and occupy a unique and pivotal place. Of their various products and services, one of the most important is the residential mortgage and it is this intellectual or human capital (the terms IC and human capital have been used synonymously for this analysis) that drives it and possibly makes it successful. All banks lend funds and have several schemes for residential mortgages, but how many are doing it successfully or recognising that it is human capital that adds the value to their products? Further, there is no evidence of measuring the enhancement of social capital in New Zealand through mobile mortgage managers (MMMs), and their value in creating the rich tapestry of social and political well-being.

Simply put, IC in banks is the vested human capital that builds or expands the customer capital base. In recent years, MMMs in New Zealand banks (NZ banks) have become one of the important means of building a customer capital base. They are a principal generator of revenue, through helping create continuous revenue over a long period of time. Therefore, they are an aid in managing and improving bank profitability. The profitability generated from the IC contributed by the MMM category can be measured directly or indirectly and hence it can be managed.

The main objective of this paper is to investigate how NZ banks incur the cost of acquiring IC and realise the need to recognise related cost drivers (e.g. research and development (R&D), recruitment, maintenance and retention), but are not spending much time or capital on assigning values to MMMs.

The paper also identifies and analyses the important cost drivers that provide insight into the suggested cost-benefit analysis approach and develops a value-creation model in accounting for IC in NZ banks. This can be applied to any human capital-related area in a service industry (e.g. an insurance company or an educational institution) or to any commercial enterprise having a customer base as one of the strands of its capital.

To achieve these objectives an investigation of the following issues was conducted:

(i) the major types of cost traceable to MMMs in NZ banks

(ii) the percentage of residential mortgage business brought in by MMMs from 1999–2006

(iii) whether MMMs add value to the mortgage products.

This paper acknowledges that the social and political underpinnings of capitalism cannot be ignored. Also, the social conflict between labour and capital that is fundamental to capitalism cannot be isolated. Having said that, despite the importance of the above it is not possible to explore value creation on the basis of critical and normative theories in this paper due to the type of information available from the banks.

The paper discusses the constituents of estimating the value of IC and contextualizes it in the MMMs initiative in NZ banks. The author provides an overview of techniques for IC valuation, with particular reference to the work of Baruch Lev, Bob Woods, Ramona Dzinkowski and Ante Pulic. That overview is followed by Methodology and links between the theory and the model. The paper then presents some insights into the banking sector and the IC vested in MMMs. Further, against the backdrop of the insights and empirical findings of the MMMs, a comprehensive, simple, straightforward and user-friendly value-added model is suggested. Finally, in the context of product differentiation and change driven by globalization (lifestyle implications, technological advancement), the Conclusions and scope for further research are outlined.

With regard to IC, over the years many definitions, indicators and measurement techniques have emerged. Some of the widely accepted and all-inclusive definitions encompass organizational (structural) capital; innovation and structural capital; human capital; relational (customer) capital; and social capital. Our ability to understand and measure intangible assets and intellectual capital has progressed greatly in recent years. Some examples of ground-breaking research in this area are the Q model developed by the Nobel Laureate economist James Tobin in the 1950s, the invisible balance sheet (Sveiby, 1989), the balanced scorecard (Kaplan & Norton, 1992), Skandia NavigatorTM (Edvinsson & Malone, 1997), the VAICTM model (Pulic, 2000), IC-Index (Roos, Roos, Dragonetti & Edvinsson 1997), Direct Intellectual Capital (Anderson & Mclean, 2000) and IC Rating (Edvinsson, 2002)

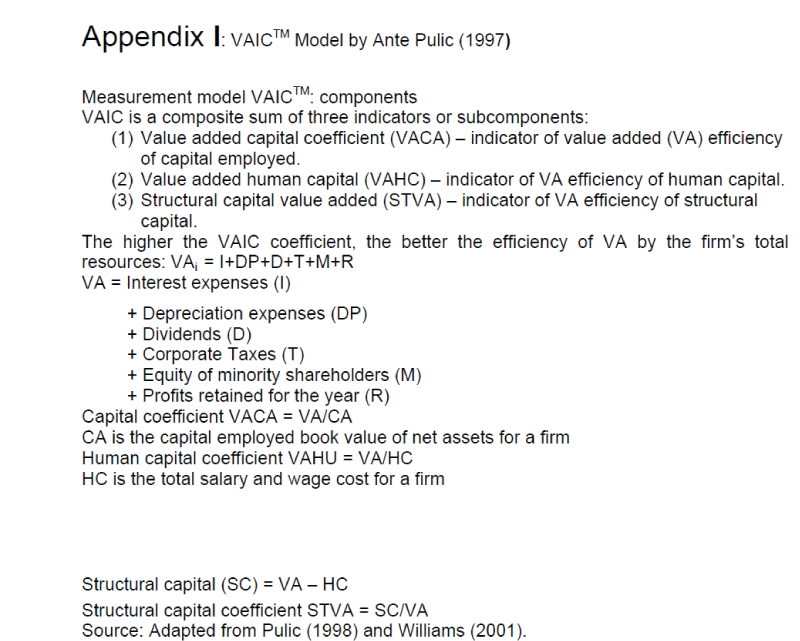

Pulic (1997) developed the VAICTM model to measure the extent to which and how efficiently IC and capital employed create value based on the relationship between capital employed, human capital, and structural capital. Williams (2000) used the VAICTM model and recognised it as a ‘universal indicator showing abilities of a company in value creation and representing a measure for business efficiency in a knowledge-based economy’ (Pulic (1998) – see Appendix I). Schneider (2000) supported the adoption of this technique as an effective method of measuring IC through the VAICTM model.

One of the authorities on IC is Baruch Lev. He defines IC in the following way (Bernhut, 2001, p. 17):

Any asset is a claim to a future benefit, such as rent from owning a commercial property. An intangible asset is – if it is successfully managed – a claim to a future benefits that does not have a physical or financial embodiment. When that claim is legally secured, as with a patent or copyright, it we generally call that asset ‘intellectual property’.

There has been considerable research on IC management and valuation techniques embedded with complex and intricate issues on constituent elements. Researcher Baruch Lev, having initiated the value creation scorecard, is now campaigning the knowledge capital earnings Methodology and is finding ways to provide intangible asset valuations corresponding with the financial reporting hypothesis. Critical accounting advocates have admitted and acknowledged the empowerment of middle-class intellectuals as administrators of hegemony, as conceived by Gramsci (Strinati, 1995). The Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants recently conducted a survey that shows that top executives of the Financial Post 300 firms in Canada and the Fortune 500 firms in the United States consider IC to be a critical factor in a firm’s success.

With respect to IC, it is very difficult – even with patent laws – to appropriately secure and derive all the benefits from the assets. This weighs heavily on accountants because for something to qualify as an asset it must control the benefits. But you don’t really control the benefits from training employees or labour, for example. So it is said, ‘Well you may get benefits from it from time to time, but you don’t control it, so it’s not an asset’ (Bernhut, 2001, p. 18).

A unique aspect of IC is that it contains no markets. There is no market in processes and no market in human assets, except where ‘headhunters’ focus on senior management, directors and CEOs, making it riskier and more difficult to manage and value these assets. At the same time, it is only by applying market values to human capital that banks in New Zealand compete with each other when hiring human capital or labour or mortgage managers. This type of competition, given New Zealand’s small population (approximately 4.2 million population) within which the same people are moving from one organisation to another, and the human and social capital enrichment, may be seen as debatable.

The market provides guidelines for valuations, so investment bankers or employment markets, when valuing companies for initial public offerings (IPOs), usually look at what are known as ‘comparable’ or similar company valuations. Due to competition in hiring appropriate mortgage managers, and the lack of specific value measurement, the valuation of these assets involves subjectivity.

Recognized authorities on IC like Baruch Lev, Bob Woods and Ante Pulic have created techniques to measure intellectual capital. Notwithstanding the many advantages of these techniques (like those for intangible assets such as brand equity and copyrights), the methodologies for measurement and management of IC have their application problems and limitations.

At a brainstorming round-table conference, ‘Leveraging Your Hidden Brain Power’ (hosted by Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu), the theme was: ‘Harness your company knowledge before it walks out of the door – and takes your business with it’ (Haapaniemi, 2001). In their Conclusion, attendees at the round-table conference agreed: ‘knowledge management – sharing intellectual capital, leveraging intellectual capital, however you want to describe this process – can produce another amazing round of productivity improvement’. Or, as stated by Zhou and Sun (2001, p. 19):

Generally, intellectual capital refers to the difference between a company’s market value and its book value. It consists of organisational knowledge and the ability of the organisation’s members to act on it. IC is often used synonymously with the terms intangible assets, intellectual assets or knowledge assets.

Lev developed a Methodology for valuing intangible assets that consists of three parts: measurement, drivers and validating usefulness. The basis of the Methodology is generated by three major inputs: physical assets, financial knowledge and intangible assets.

An Australian project entitled ‘Are companies thinking smart?’ (Guthrie and Petty, 2000), based on empirical aspects, applied a popular model – the Intangible Asset Monitor, developed by Karl Erik Sveiby, wherein Sveiby classifies firm intangibles into three elements. Firstly, Human Capital: represented by human resources (employee competencies), which are broadly related to education and training of professional staff, who are the principal generators of revenue. Non-revenue generators are called support staff. Employees create value by applying their skills, exerting their knowledge and initiating new ideas. It’s a matter of transforming their tacit knowledge into explicit variety. Secondly, Structural Capital: related to internal structure, which includes organisational structure, legal parameters, manual systems, research and development and software systems. Thirdly, Customer Capital: related to external structure, which includes items such as brands and customer/supplier relationships. It also includes customer loyalty and organisational reputation.(Adapted from Karl Sveiby’s developed Framework (1997).)

In the abovementioned Australian project, the percentage breakdown of the IC of 70 companies was represented as follows: 40 per cent reporting external capital, 30 per cent the internal capital structure, and 30 per cent the human categories. The skew towards external (customer and relational) capital items was greatest, proving that in recent years rationalizing distribution channels, reconfiguring firm value chains and reassessing customer value have increased in importance. The internal and human categories were evenly matched at 30 per cent each.

Human capital can be interpreted as the engine of intellectual capital, with structural capital providing the support and customer capital deriving benefit from human and structural capital. Banks and financial institutions, which are rich in intellectual capital stock, need to create an environment in which people (human capital) can produce extraordinary results (customer capital).The sum total of this forms the basis of social capital and raises questions about how to sustain this social capital in a political and capitalist environment. The core idea of social capital is that social networks have value. The value of networks is not exactly measurable, but they do increase productivity, both individual and collective. Jane Jacobs tried to define social capital in the 1960s as the ‘value of networks’. Portes (1998) identified four negative consequences of social capital. On this basis, and with other established research, it is an economic concept of human capital (see Fig. 1 Influences on the process of economic growth).

Notwithstanding the immense importance of external (customer and relational) capital, it is important to remember the following:

(a) Customer capital is also an intrinsic part of social capital. Social capital theory is based on the core idea that social networks have value. Just as structural capital and human capital can increase productivity, so can social contacts affect productivity? Unlike economic capital, social capital does not deplete on use. In fact, it is based on the reverse analogy – it depletes by non-use (‘use it or lose it’). In the context of mortgage managers, the process of sourcing funds is achieved via a procedure known as securitization. This is a process whereby assets (such as mortgages) with an income stream are pooled and converted into saleable securities These assets are purchased and packaged into low-risk, negotiable securities such as bonds and then issued to investors. The MMM’s job is to set up the loan and perform a liaison role with all parties involved, namely originators, trustees, credit assessors and the borrowers providing the customer service role. Having said that, NZ banks do not follow the securitization procedure.

(b) Customers can be bought and sold in terms of explicit valuation of future sales, and the potential of specific customer groups is increasingly an important component of merger and acquisition decisions (Schmittlein, 1995).

(c) With the increase in internal sales (business to business) in the area of electronic commerce, customer loyalty has become a greater challenge. Today’s customer is exposed to a huge variety of advertisements, competing firms, products, brands and price wars.

Therefore, IC includes traditional intangible assets such as brand names, trademarks and goodwill and new intangibles such as technology, skills and customer relationships. These are resources that an organization could – and should – make the most of, in order to obtain competitive advantage (Zhou & Sun, 2001).

The New Zealand banking industry is rich in human capital and customer capital. The industry should try and optimise the advantages accruing from this intellectual capital. Mobile Mortgage Managers provide the banks with the benefits of managing customers as strategic assets. The customers include loyal customers who are less inclined to shop around or buy mortgages at a given price, for a more efficient, effective, highly targeted and focused customer base (Schmittlein, 1995):

It is this customer who provides a stable predictable source of revenue, future revenue and can be reliably differentiated from each other based on his/her behaviour.

Customer networks form one of the main lenses of social capital in the banking sector context in New Zealand, as in most other countries. Despite the overhyped secrecy surrounding information sharing, banks seem oblivious to the role that is played by MMMs in structural capital and labour savings on the one hand and contributions to the social capital in the form of value addition by customer networks on the other hand. From discussions and interviews conducted it emerged that banks were blissfully ignorant, and wished to remain so, about assigning direct and indirect value additions by MMMs. Acknowledging the value addition may cause pressures on management and capital that employers were not ready to deal with. Simply put, it is not on the banks’ agenda, due to cumbersome consequential costs and information they may have to deal with or disclose.

The MMMs of the big NZ banks represent the walking, talking intellectual skills that have brought in a huge customer capital base. Since 1996, they have added a completely different flavour to the mortgage business in New Zealand through their creative networking. The personalised networking and Methodology may be old, but the style is new. Their innovative strategies have produced unexpected results and yet they are not recognized as contributors enriching the social fabric of communities they are serving in terms of value creation and ultimately measured through some form of accounting. MMMs in New Zealand are not appreciated as high-value contributors to the social capital environment, even though mortgages are one of the intrinsic and basic lifestyle choices of New Zealanders.

Traditionally, the banking industry has a dual driver, unlike manufacturing companies or industries, where the main driver is the product. In banking there is a three-dimensional and three-phased process on the one hand – the organization, product and accounts – and on the other hand there is the service driver, which has its wealth in customer capital. The cost of funds in a bank, like the cost of goods in a manufacturing firm, represents the cost of producing and selling a product. While in manufacturing there tends to be a reduction of production costs per unit as fixed costs are more widely spread with increased production (up to a certain point), this is not so in banking operations (Kiran, 1986).

Efficiency in the banking industry is measured through traditional ratio analysis (for example, earning ratios, expense ratios) and through simple productivity parameters like deposits per employee, advances per employee, mortgage business per manager, total business per employee, and expenses per employee.

Funds used efficiently owing to high productivity of personnel will lead to high profitability. Productivity is an input/output ratio. When we talk of productivity, we enter into the area of employee efficiency, which has a bearing on profitability. Some bank managers feel that one or all of the following could improve profitability in general:

(i) Internal efficiency: – Operational efficiency – Managerial efficiency (that is, efficiency of management control). (ii) External efficiency (that is, efficiency in dealing with customers).

These are interrelated to a certain extent. It is well known that external efficiency is of prime importance in the banking industry.

In general, therefore, a drive for continuous productivity improvement, especially in the Internet economies, is a challenge to the banking sector. The VAICTM method measures and monitors the value creation efficiency in a company using accounting-based figures (see Appendix I). The better a company’s resources have been utilized, the higher the company’s value creation efficiency will be.

The efficiency of NZ banks in serving customers has been driven by technological advances in the last few years. In New Zealand, electronic funds transfer at point of sale (EFTPOS) terminals have grown in number from 46,360 in 1996 to 84,351 at the end of 2000 (Detoured, October 2001, p. 6). However, there are customers who prefer traditional ‘across-the-counter’ and ‘face-to-face’ relationships, and these results in different levels and quality of productivity.

In banking, customer capital refers to the organization’s relationship with outside parties. It includes customer loyalty, the organization’s reputation and its relationship with suppliers, partners and/or other stakeholders. Customer capital is the organization’s ability to meet rapidly changing customer needs, to provide knowledge and financial service to customers and to capitalise on their relationships with outside parties (Zhou & Sun, 2001, p. 19).

It is this customer capital approach that some of the big banks in New Zealand have adapted and refined that has added more value to important, high income generating mortgage business through MMMs. They operate in an almost free business environment, capitalising on their abilities and using traditional relationship-building techniques of servicing customer needs and assessing customer satisfaction on an ongoing basis. It is important here to concede the importance of social capital. The lens of customer capital as part of social capital is important for both the microeconomic and macroeconomic environments, especially capitalist economies, which are based on social and political underpinnings. Another important lens to be recognised lies in the relationship of income and capital, which cannot be ignored when discussing value creation. The customer provides the ‘income’ and is the essential contributor to the survival of the banking sector. In New Zealand, MMMs are one of the main catalysts or mediums through which considerable cash flows are injected into banks at the micro level and the financial market at the macro level. Hence, by engaging with customers the MMMs are facilitating, supporting and promoting social, cultural, and political stability, as well as motivating society to do better through investments in real estate and thereby lead a higher quality life through property ownership. Among the many positive dimensions, MMMs are also providing sustainability through quality of life, risk-adjusted rate of return (to both banks and their customers), collateral benefits and security for future generations, and this is yet another lens of the social capital, responsibility and social accounting framework. This is also in sync with Maslow’s pyramid of needs, security, self-esteem and so on. However, this aspect is beyond the scope of the present investigation.

Mobile Mortgage Managers

Mobile Mortgage Managers are people who are helping other people to achieve one of their major goals in life. They are driven individuals who work closely with the retail networks and have the ability to proactively network while developing new business opportunities. They have almost unlimited earning potential. Their success, however, depends on self-motivation, excellence in maximising customer retention, a technical and flexible approach to working hours and most importantly having a ‘can-do’ attitude along with outstanding relationship management skills and networking capabilities. They may or may not have a background in the finance and property sector. They are given training and have the capacity to earn commissions on NZ$2–5 million plus loans monthly.

The ANZ National Bank was a pioneer in employing MMMs in New Zealand. It started in 1996 with approximately 20 MMMs and this figure had risen to 52 in December 2006. The BNZ has the second highest number of MMMs. Some of the specific features of value addition through the use of MMMs in New Zealand banking that emerged from interviews with bank staff and MMMs are as follows:

• Relationship marketing: MMMs work on a one-to-one basis, using the most personalised retail sales technique, in the form of relationship building. It is like the haute couture or boutique business, where the word of mouth of an already satisfied and known customer is enough to encourage others to become customers. The average New Zealander changes their house and reorganises their mortgage arrangements six to eight times in their lifetime.

In New Zealand, taking out a mortgage is a comparatively frequent and compulsive decision that affects the person’s lifestyle and makes a social statement. A satisfied customer’s communication is significant. A customer communicating satisfaction to a friend or colleague has greater influence on whether or not that friend or colleague becomes a customer of the bank or MMM. A customer gained through the recommendation of another customer is already in a positive frame of mind and is more easily satisfied by the MMM.

•Value addition: MMMs add value to the mortgage by working closely with other retail networks and facilitating sales of other related products like insurance (life, property, and contents), credit cards, loyalty programmes, holiday packages, furnishing sweeteners and so on. They end up developing new business opportunities through proactive relationships. The big influx of MMMs into the marketplace in recent years has substantially heightened competition and enhanced global communication.

• Adding brand equity: MMMs help the customer to make decisions and choices through their selling techniques for specialised products, like fixed-interest, floating-interest and flexi-interest loan accounts (these are the brands in one New Zealand bank, the ANZ National Bank – others, like the BNZ, sell air points through global access credit cards, and Fly Buys points for mortgage installments).

• Time management: MMMs have the special advantage of flexi time and are thus able to accommodate a customer at the customer’s convenience. They are self-driven individuals who want to work for themselves but are employed by a particular bank. They are not mortgage brokers who work on their own but sell mortgages for several banks at the same time. Unlike mortgage brokers, MMMs do not have a range of choices of different banks for their customers.

• Better verification: MMMs have the hands-on advantage of verifying the creditworthiness and credibility of the customer by personal interaction, as they are able to visit the client’s home and workplace. They get to know their client better than a branch consultant (BC), who stays at their office. They can, therefore, conduct a more rigorous loan and client appraisal. Their relationship management skills and networking ability makes verification easier.

• Price competitive: MMMs are price competitive for a number of reasons. They have substantially lower overheads than the BCs working from bank premises. They have no extensive branch networks or shop fronts, as they do not have deposit facilities. Obtaining funds via the securitization process and low overheads often allow MMMs to undercut the bank’s rates. In more recent times increasing numbers are offering comprehensive products with numerous features that increase the flexibility of the loan. MMMs normally operate from home and therefore save the bank a considerable cost for space, although banks compensate MMMs by giving them a car and reimbursing them for other maintenance costs (not a common benefit in the New Zealand private sector).

• Increasing market share: MMMs have a better opportunity to add on a segment of customers who would otherwise be left out – those who state ‘I’ll find out’, but don’t follow this up. Such a customer probably comes their way easily through the network of solicitors, estate and insurance agents, registered valuers and builders.

• Comparative analysis: The flexi time, mobility and freedom gives MMMs the time to make comparisons with other banks’ mortgage products and to analyse other qualitative issues. This matters more in competition, where the product generates a high income (for example, average mortgage funds advanced range from NZ$200,000 to 300,000). These reports help the banks to maintain a competitive edge and improve their own policies.

• High-level motivation: Instant commissions on top of fixed salaries and benefits keep MMMs happy and motivated to achieve higher targets. They feel rewarded and respected and pass on their satisfaction to their customers, who in turn pass on their satisfaction and thereby bring in more potential clients. (For the purposes of this paper the words ‘client’ and ‘customer’ have been used synonymously.) Motivation also improves the quality of social networks and value.

Empirical analysis

The mortgage business on an overall basis for the 17 registered banks in New Zealand showed residential mortgages formed 46 per cent (NZ$55,670 million) of the total loans and advances in 1999 and 50 per cent in 2006 (Table 1). Between 1999–2006 the percentage ranged from 46 per cent to 51 per cent. Most of the registered banks are foreign banks (non- New Zealand and Australian banks), with the exception of Kiwi bank, and generally do not employ MMMs for residential mortgage business. A few foreign banks that have initiated this service in recent years are not willing to disclose the amount or percentage of business generated by MMMs. The proportion of bank lending to households has increased from 34 per cent to 44 per cent between 2001 and 2005, increasing alongside the cyclical pick-up in house prices for the four major registered banks (ANZ National, ASB, BNZ and Westpac). During the December 2005 year, NZ$16 billion was attributable to residential mortgages, following on from NZ$12.5 billion in each of the preceding two years. The earning yield of the four abovementioned banks on loans and advances was approximately 7.77 per cent in 2004 and 8.10 per cent by the end of 2005 (Reserve Bank of New Zealand, 2006, p. 47). It is an established fact that mortgage lending is generally viewed as lower risk than corporate lending: the loans are for low amounts relative to corporate loans and are spread across a large number of borrowers. Having said that, there are some risks and risk-management challenges associated with residential mortgage lending. For example, rapid growth in residential mortgages could compromise the quality of risk monitoring or management services in other parts of banks’ balance sheets. Despite the importance of the risk-management issues, they are outside the scope of this paper.

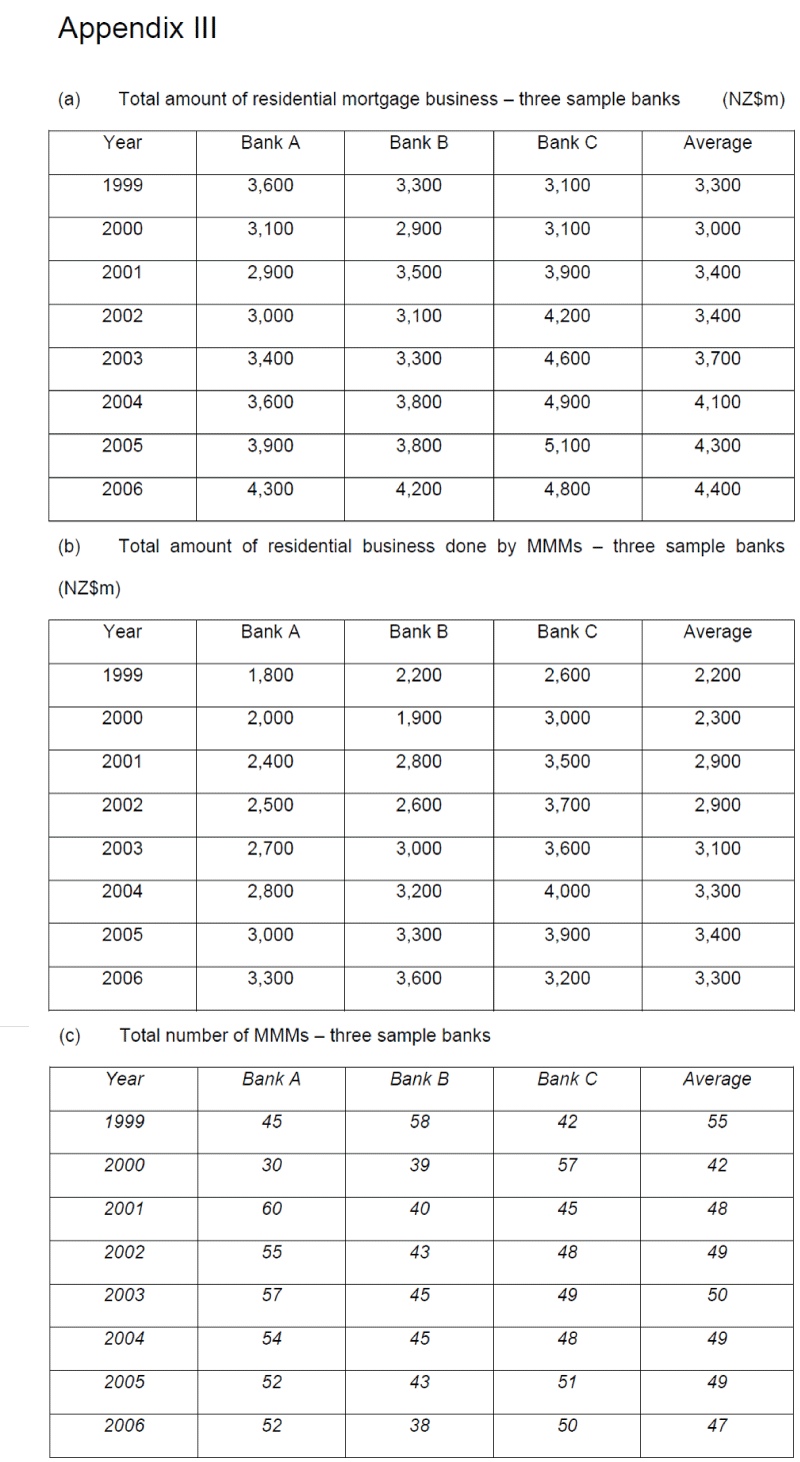

For the three sample banks (see Table 2) during 1999–2006, the residential mortgages business generated and attributable to MMMs ranged between 66–85 per cent. The balance of 14–35 per cent of business was brought in by the mortgage managers and independent mortgage brokers. The average productivity of an MMM during 1999–2006 for the three sample banks was approximately NZ$60 million per annum. However, the static mortgage managers’ or BCs’ average output was approximately NZ$17 million per annum. Therefore, the productivity of MMMs in terms of advances per employee is much higher (almost 30 per cent more) than the productivity of BCs and independent brokers put together.

Of the 52 MMMs in the ANZ National Bank (one of the three sample banks) during the year 2006, approximately 22 were very aggressive (those producing more business than the average). In most of the banks each MMM is doing an average business of NZ $2.5 million a month, although three or four bring in NZ$6 million per month. By 2006, the average business of an MMM had nearly doubled to approximately NZ$5 million per month, whereas the number of MMMs had increased by only 7 (total 45 in year 1999).

The total business produced by MMMs for the three sample banks has increased by nearly 33 per cent over eight years. The impact on productivity of advances per MMM in the year 2006 is nearly twice that of the year 1999. It is important to mention here that overall residential property prices have increased by nearly 40 per cent during the same period. The analysis of the increase in property prices is outside the scope of this paper.

The average number of MMMs in the three banks has ranged from 42 to 55 in number (Table 3). The percentage of average business generated through MMMs has increased from 66 per cent in 1999 to 85 per cent in both 2001 and 2002. The average percentage of business produced by MMMs for the three sample banks has dropped from 84 per cent in 2003 to 75 per cent in 2006 (Table 2). This is probably attributable to Bank B, which reduced the number of MMMs employed due to internal policy changes (Appendix III – the figures shown in Appendix III for the three sample banks have been rounded off to keep the anonymity of banks). This bank has engaged more BCs to handle premium business clients (customers with higher mortgage business) for its branches by increasing salary packages to motivate them.

This move was perhaps due to the increasing rivalry and aggressive competition in hiring MMMs among the five main banks in recent years. MMMs were increasingly walking in and out of banks and negotiating higher remuneration packages corresponding to their IC (customer and social networks) on the one hand and the aggressive property market in New Zealand on the other hand.

Successful MMMs have a unique way of networking with customers and branch consultants. The relationship or team-building skills between the branch banking consultant (BC) (the static loans or mortgage manager) and the customer comes second. Sometimes a customer who is ready to sign may suddenly be put off by a little carelessness on the part the BC and walk out. Interview data has shown many times that a little negligence on the part of an MMM towards the end of the deal has also cost them time, money and loss of reputation and, therefore, future business.

One cannot ‘buy it’ – one either ‘has it’ or ‘hasn’t got it’. Some skills cannot always be acquired through training. As highly skilled bank staff, MMMs cannot afford to be careless or negligent because of the time invested in a client. Only when the deal is through and all the add-on products (essential to complete the deal) sold to the customer, arrangements for follow-up by the concerned accounts manager made, and the actual disbursement of the loan on the settlement day made, can an MMM claim the particular mortgage arrangement as their business. This is the time when MMMs make commissions.

When an MMM gives the best deal and gets the next referral customer, they may consider their added value to the bank and the bank in turn must recognize the intellectual capital vested in this MMM. As opposed to MMMs, the BC may work most efficiently in the safe and secure environment of the bank branch, but be uncomfortable outside it. In New Zealand’s multicultural environment, where the customer base consists of Māori, Pacific, European, Chinese, Japanese and Indian people, one of the recognised add-on qualities of an MMM is their ability to relate to diverse cultures and to be bilingual where necessary. A loan and customer may be lost when a BC does not give the customer sufficient time, because of routine branch pressures and the consultant’s unwillingness to work outside a set routine. Banks in New Zealand are increasingly hiring MMMs from different ethnicities to reach out further and provide additional and specific services relevant to the culture of the client, as long as the mortgage arrangement is within policy limits and the requisite documentation is completed to the satisfaction of the bank.

Two approaches to asset appraisals for value creation

The cost of an asset doesn’t change once it is purchased. The value of an asset like a brand name can change. Consider Ipana toothpaste or Burma shave. These were well-known brands 40 years ago, but now they have only historic interest. Yahoo or Amazon.Com are two of the most valued brands in electronic commerce today, and no one had heard of them a few years back (King & Jay, 1999, p. 36).

The cost approach

If, in the New Zealand real estate market, bank loans or mortgages and valuations are examined, it will be noticed that the cost of the asset (that is, the house/building) has not changed, but the value is changing every year. The government adds value by appraising almost the entire real estate of New Zealand every year (varying estimates according to demand and location and so on). It gives the client a loan based on the Registered Value (RV) or Government Value (GV) today, which has nothing to do with the actual cost of the asset.

Houses or personal property are a tangible asset. Yet, if the depreciation is to be accounted for, the value should be nil for a 25 or 50-year-old house today. But here the value is the price a purchaser will have to pay to build the same building today. A purchaser wouldn’t acquire an existing house at a NZ$150 per square meter if a new house could be constructed at NZ$100 per square metre.

The cost approach is considered to be reliable when dealing with tangible estates like real estate.

The notional approach

This is a market-based approach comparing similar assets or products and their selling prices – for example, how would one value a 1999, four-door BMW? A comparison with models of the same horsepower and vintage and with other similar features will establish a market value or sale price. This approach can also be used for well-established products and for consumer durable intangibles like technology, skills and customer relationships. These are the resources in which is vested the very foundation of banking in the new economy.

Copyright © 2025 Research and Reviews, All Rights Reserved